Mali in Crisis: A Nation at the Crossroads of Terror, Resistance, and Imperialist Pressure

Mali today finds itself on the brink of collapse under the weight of an escalating Islamist insurgency, geopolitical isolation, and economic strangulation. For over two months, the Islamist militant coalition Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) has imposed a near-complete fuel blockade on the capital, Bamako. Despite military efforts to secure fuel routes from Senegal and Ivory Coast, relentless ambushes on fuel convoys have cut the city off from vital energy supplies.

This blockade has sparked a chain reaction of social and economic disruption. Schools have shuttered, hospitals are operating under dire conditions, and businesses dependent on fuel for power have ceased operations. Citizens now endure days-long queues for limited and exorbitantly priced fuel. Even the military’s capacity for long-range operations is now severely impaired. The fuel crisis is not just a logistical challenge; it’s a symbol of the broader unraveling of state power.

The Rise of Islamist Insurgency: A Post-Imperialist Crisis

The roots of Mali’s crisis trace back to the NATO-led intervention in Libya in 2011. The overthrow of Gaddafi unleashed a torrent of weapons and fighters across the Sahel, dramatically escalating the Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali. However, what began as a national liberation struggle was quickly overtaken by jihadist forces linked to Al-Qaeda.

In response, France launched Operation Serval in 2013 and later Operation Barkhane, which ballooned into a 5,000-strong foreign military presence. At its peak, there were nearly 20,000 French and UN troops in Mali. Yet, despite this overwhelming foreign deployment, Islamist groups extended their control over more than two-thirds of Malian territory, expanding into Burkina Faso and Niger and leaving behind a trail of massacres, forced marriages, and displacement.

Today, over 30,000 people have been killed and four million displaced due to the Sahel’s spreading insurgency—a tragic indictment of Western interventionism that failed to address the social roots of extremism and instead exacerbated them.

Popular Uprising and the Military Break from the West

Years of corruption, repression, and imperialist subservience by the Keïta regime eventually triggered a mass protest movement in 2020. The attempted constitutional coup by President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was the final spark. A mass uprising, led in part by the M5 movement, culminated in his ousting by a military coup.

Initially welcomed as a step toward change, the transitional government failed to deviate from the status quo and was soon replaced by another coup led by Colonel Assimi Goïta. His new government broke decisively with France and other Western backers, ejecting French troops and aligning instead with Russia, notably inviting Wagner Group mercenaries to aid the fight against jihadists.

Goïta’s move toward sovereignty gained popular support. Sanctions from ECOWAS and the suspension of diplomatic ties by France did not dampen the military government’s resolve.

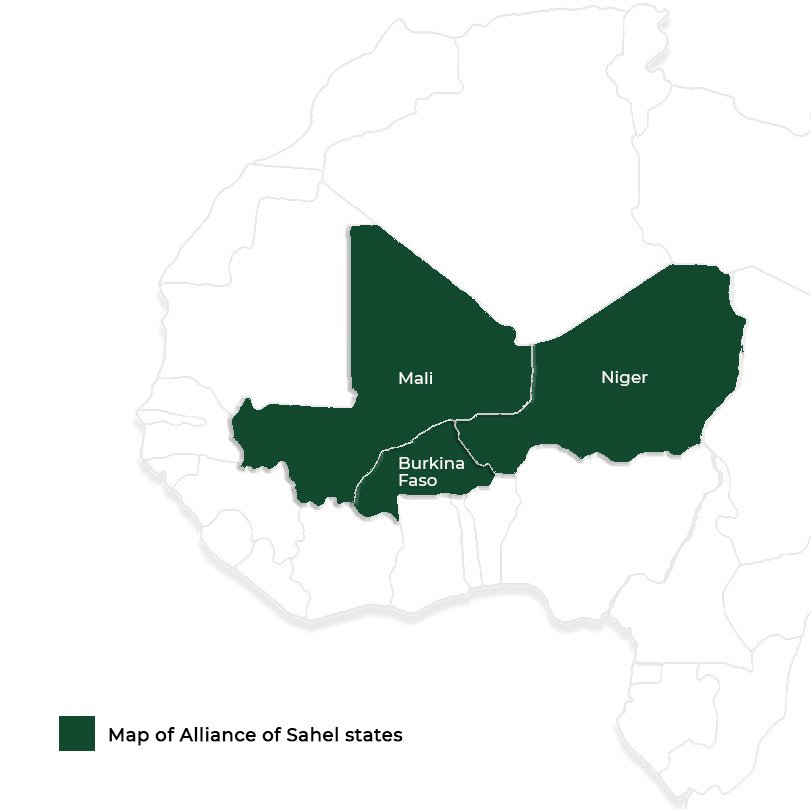

Rather, it spurred deeper anti-imperialist sentiment and the formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) with Burkina Faso and Niger in 2023, aiming to resist both jihadist advances and imperialist interference.

The Contradictions of Mali’s Anti-Imperialist Turn

Though Goïta’s government offered a break from imperialist domination, it remains constrained by its adherence to capitalism. The AES governments, while promising sovereignty and reform, are authoritarian and maintain capitalist economic structures—limiting their ability to address the root causes of crisis.

Nevertheless, some bold moves have been made. The AES states have rewritten mining laws, raised taxes on foreign multinationals, and threatened to revoke licenses for non-compliance.

In Mali, Goïta’s administration even seized gold from Barrick Gold, the world’s largest gold miner, after it refused to meet the new royalty terms.

These acts—though limited—reflect a popular desire for national control over resources. But they also highlight the limits of nationalism under capitalism, especially in regions with weak infrastructure and no sovereign control over key sectors of the economy.

JNIM’s Deep Roots and the Crisis of State Power

Despite aggressive military operations and Russian support, Goïta’s government has failed to dislodge JNIM. In part, this is because jihadist groups are not merely insurgents; they have become de facto governing authorities in large swaths of rural Mali. In regions where the state is absent, jihadists mediate land disputes, run protection rackets, and control key economic flows such as smuggling and artisanal mining.

These networks are embedded in both the licit and illicit capitalist economy. Stolen cattle are trafficked into Ghana and Ivory Coast for sale. Gold from jihadist-controlled mines is smuggled across porous borders to meet global demand. These criminal economies sustain the insurgency, making purely military solutions unviable.

Meanwhile, rural poverty fuels jihadist recruitment. For many young men, joining the insurgency provides a livelihood in a system where the state offers nothing. In this context, counterinsurgency efforts face structural limitations—without economic transformation, militancy remains a rational survival strategy for the impoverished.

Wagner’s Exit and Russia’s Limited Aid

hough Mali initially looked to Russia for military and economic support, the partnership has frayed. Wagner mercenaries, having faced severe losses and denied access to Mali’s gold sector, have largely withdrawn. Their presence had already caused controversy due to high civilian casualties and questionable conduct.

Russia’s remaining forces—mainly trainers—are insufficient to reverse battlefield dynamics. Although Moscow announced a deal to deliver 200,000 tons of petroleum and agricultural products in late October, little has materialized. As of now, no substantial deliveries have been confirmed, and Mali’s economic clock continues ticking toward collapse.

Isolation and Regional Sabotage

Western-aligned states like Ivory Coast have refused to protect Malian supply routes, effectively allowing JNIM to intensify its siege. ECOWAS, which once threatened military intervention in Niger, has remained hostile to the AES bloc. Some member states, such as Ghana, are allegedly cooperating with foreign powers to undermine these governments.

This isolation has created fertile ground for JNIM’s political ambitions. The group has distanced itself from overt references to Al-Qaeda and may be positioning itself for international legitimacy, mirroring strategies used by groups like Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in Syria.

Impending Collapse and Dangerous Precedents

The Malian government is at a breaking point. If the blockade continues, the collapse of Goïta’s government becomes increasingly likely, either through internal dissent, a new coup, or negotiated surrender. Already, local authorities have been authorized to negotiate with JNIM—a quiet admission of retreat in many rural areas.

Such a collapse would have disastrous consequences. JNIM could institutionalize its parallel state, impose Sharia law, and trigger sectarian conflict between ethnic militias and Islamist forces. The precedent would be dangerous not only for Mali but for the entire region. In neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger—also part of the AES—instability in Mali could embolden jihadist groups and encircle key cities like Ouagadougou.

Reports of JNIM attacks in Benin and even Nigeria in recent months confirm the insurgency’s growing reach. If Mali falls, West Africa could see a new era of jihadist expansion.

Military force alone cannot solve Mali’s crisis. Nor can alliances with foreign powers—be it France, Russia, or anyone else. The root of the problem lies in capitalism, which has made West Africa dependent, impoverished, and vulnerable to extremism.