As President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva advances through his third term, Brazil, Latin America’s largest nation, finds itself once again mired in a leadership crisis. Once celebrated as a transformative figure of the left, Lula now presides over a government suffering from declining public approval and mounting political fatigue.

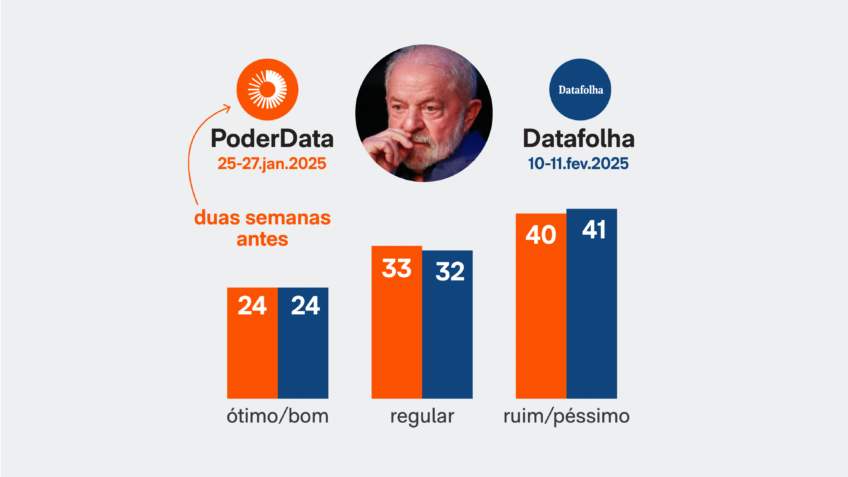

According to a reputable February survey conducted by Datafolha, only 24 percent of respondents rated Lula’s government positively, while 41 percent expressed disapproval, and 32 percent described it as “average.” Other polls mirror this trend, painting a portrait of a gradual but undeniable erosion of support for the historic leader of Brazil’s left.

Lula’s honeymoon period, which was buoyed by high expectations but accompanied by few flagship policy triumphs, has ended. He now grapples with the same broad dissatisfaction that has felled every Brazilian presidency since he last departed office in 2010. Deepening political polarisation, an entrenched conservative-dominated Congress, and the inability to engage a new generation of workers, have all contributed to perceptions that Lula and his Workers’ Party (PT) are faltering.

More troubling still, Lula and the PT have yet to identify or cultivate a credible successor. As the 2026 election looms and public desire for renewal intensifies, the odds of the Brazilian left retaining power appear increasingly remote.

From Broad Consensus to Political Instability

Brazil’s political environment over the last decade has been marked by turmoil. The previous three presidents—Dilma Rousseff, Michel Temer, and Jair Bolsonaro—though ideologically distinct, all ended their terms under clouds of profound unpopularity. While each faced their own particular crises, their collective downfall reflects the broader fragility of Brazil’s political order, which has been particularly unstable since Lula concluded his second term in 2010.

When Lula stepped down after eight years in office, he did so as one of the most popular political leaders globally, boasting an 87 percent approval rating in one poll. His legacy was so luminous that it once prompted Barack Obama to refer to him at the G20 as “the most popular politician on Earth.”

However, Lula’s rise and his policies were never universally embraced. His progressive agenda, aimed at eradicating poverty and expanding social welfare, met fierce opposition from Brazil’s entrenched elite and segments of the middle class. Lula, a former metalworker from the impoverished Northeast who never attended university, stood in sharp contrast to Brazil’s traditional presidential archetype: elite, well-educated, and politically bred.

The 2005 Mensalão scandal rocked Lula’s government, thrusting accusations of corruption to the forefront of public discourse. Mainstream media, especially the powerful Globo conglomerate, seized on the scandal, amplifying criticism of Lula with a fervour rooted as much in class animosity as in journalistic scrutiny.

Nonetheless, Lula’s exceptional skill in building broad coalitions enabled him to maintain parliamentary support and push through transformative programmes such as Bolsa Família and Fome Zero, which lifted millions out of poverty and greatly expanded access to education and healthcare. His leadership coincided with an economic boom and an enhanced role for Brazil on the world stage.

During Lula’s era, Brazil’s political terrain, though contested, was relatively stable. The ideological divide between the centre-left PT and the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSDB) was real but tempered by a shared commitment to advancing democratic institutions and pursuing economic development. Lula presided over this period of comparative harmony.

The Fragmentation of the Consensus and Bolsonaro’s Rise

The stability of the Lula years unraveled during the presidency of Dilma Rousseff, his chosen successor. Rousseff’s tenure was plagued by economic downturns and corruption scandals, unfolding just as social media emerged as a potent force for political mobilisation.

The Jornadas de Junho in 2013—a wave of nationwide protests—voiced public frustration over corruption and inequality, but also revealed a fragmented and volatile political mood. Rousseff struggled to navigate this unrest. Unlike Lula, she lacked the deftness for coalition-building, and her tenuous relationship with Congress stymied meaningful reforms.

After narrowly winning re-election in 2014, Rousseff was impeached two years later in a move that the right hailed as justice, while the left decried it as a parliamentary coup. Her successor, Vice President Michel Temer, quickly embraced austerity policies. Though despised by the left and mistrusted by the right, Temer survived through his strong congressional ties, enduring until the next electoral cycle despite abysmal public support.

By the time of the 2018 elections, Brazil had drifted far from the relative optimism of the 2000s. Years of conservative media attacks and judicial overreach had severely tarnished the PT. The controversial Operation Car Wash, while claiming to fight corruption, functioned largely as a politically charged crusade against the left, ultimately leading to Lula’s imprisonment on charges that were later overturned.

By the time of the 2018 elections, Brazil had drifted far from the relative optimism of the 2000s. Years of conservative media attacks and judicial overreach had severely tarnished the PT. The controversial Operation Car Wash, while claiming to fight corruption, functioned largely as a politically charged crusade against the left, ultimately leading to Lula’s imprisonment on charges that were later overturned.

Lula’s removal from contention opened the door for Jair Bolsonaro, a previously marginal far-right figure, to sweep to power. Bolsonaro exploited public disenchantment, presenting himself as an outsider ready to dismantle the establishment. His presidency, marred by chaos, authoritarian posturing, and catastrophic mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic, fuelled daily protests across Brazilian cities.

Lula returned to the political stage in 2022, narrowly unseating Bolsonaro. Despite the PT’s weakened standing, Lula’s personal appeal remained unmatched. Yet this victory did not herald a return to the stability of earlier years. Lula, once again at the helm, found himself presiding over a fragmented nation, unable to replicate the policy triumphs of his earlier terms. He had no equivalent to the transformational programmes of the past, and in an age of digital noise, incremental gains struggled to capture public imagination.

Navigating a Transformed Electorate

Lula’s current difficulties stem in part from the transformation of Brazil’s working class. The traditional base of factory workers and domestic labourers, once the backbone of the PT, has been partially supplanted by a precarious gig economy populated by self-described entrepreneurs who eschew collective identity.

For this new workforce—couriers, ride-share drivers, freelancers—the PT’s historic appeals to labour solidarity seem outdated. Messages about better wages and protections hold little sway for workers who see themselves as self-made individuals navigating a flexible marketplace. The right’s rhetoric of “less state, more freedom” resonates powerfully, amplified by a sprawling ecosystem of far-right influencers and social media disinformation.

A recent example illustrates this vulnerability. When the Lula administration proposed modest regulation of Brazil’s ubiquitous instant payment system (Pix)—intended to flag large transactions for criminal scrutiny—fake news rapidly spread across social media, falsely claiming the government aimed to tax or abolish Pix. The administration’s delayed response allowed the narrative to fester, forcing an eventual retreat and reinforcing the perception of an out-of-touch government beholden to unpopular decisions.

Such episodes underscore the Lula government’s struggle not just with governance, but with narrative control in an era of hyper-mediatised politics.

The PT’s Succession Problem

The PT was born as a vibrant coalition of leftist currents—revolutionary socialists, progressive Christians, and social democrats—united in pursuit of systemic change. Over time, however, it has become increasingly centralised around Lula’s singular persona, leaving a dangerous void in leadership succession.

Lula’s chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, initially rode his popularity into office but lacked his charisma and political deftness. By 2018, amid Lula’s imprisonment, the party’s reliance on its founder was stark. Fernando Haddad, Lula’s proxy candidate, failed to capture the public imagination, losing decisively to Bolsonaro.

In 2022, the PT once again turned to Lula as its sole viable standard-bearer. While he managed to edge out Bolsonaro, the absence of alternative figures within the party has become glaringly apparent as the 2026 elections approach.

Potential successors within the PT remain weak. Fernando Haddad, now finance minister, has made policy strides but lacks widespread recognition. Gleisi Hoffmann, the party’s president, commands respect but disavows personal presidential ambitions. Rui Costa, a centrist PT figure, similarly lacks the popular resonance needed for national leadership.

Meanwhile, talents from outside the PT have been sidelined. Flávio Dino, once a promising contender with a strong reformist record and national recognition, was appointed by Lula to the Supreme Court, effectively removing him from the political arena.

Lula’s 2022 running mate, Geraldo Alckmin, a former centre-right rival, symbolised an effort to broaden appeal but remains a poor fit as a leftist successor.

The resulting vacuum places the PT in a precarious position, dangerously reliant on Lula once more, despite his advancing age and explicit statements that he does not intend to run in 2026.

The Right in Disarray, Yet Dangerous

Brazil’s conservative forces are not without their own crises. Jair Bolsonaro, already barred from office for previous infractions, now faces prosecution for plotting a coup to overturn the 2022 election. His legal jeopardy leaves the Brazilian right without a unifying figure.

Possible substitutes, such as São Paulo Governor Tarcísio de Freitas, a Bolsonaro ally, or Bolsonaro’s own son Eduardo, lack the populist magnetism of the former president. Much like the PT in 2018, the right risks becoming a hollowed-out movement dependent on the image of an absent leader.

Despite this, the fragmented right continues to maintain cultural dominance, especially in digital spaces where narratives hostile to Lula and the left flourish unchecked.

2026: A Defining Test

With the next presidential election fast approaching, the Brazilian left faces a decisive juncture. Lula, should he defy age and previous declarations, remains the left’s strongest candidate. Yet his candidacy would signal a failure to renew leadership and risks deepening perceptions of political stagnation.

Alternatively, endorsing a successor would necessitate rapidly building their public profile and credibility—a formidable challenge in the face of a hostile media environment and a polarised electorate.

For Lula and the PT, the path forward demands not only effective governance but a strategic communication offensive capable of reclaiming narrative control and bridging the widening gap between policy achievements and public perception.

The battle for Brazil’s future remains open. But without bold steps to renew its leadership and rejuvenate its appeal to Brazil’s transformed working class, the left risks losing ground at a critical moment in the nation’s history.