Estonia’s Constitutional Revision: National Chauvinism Masked as Security

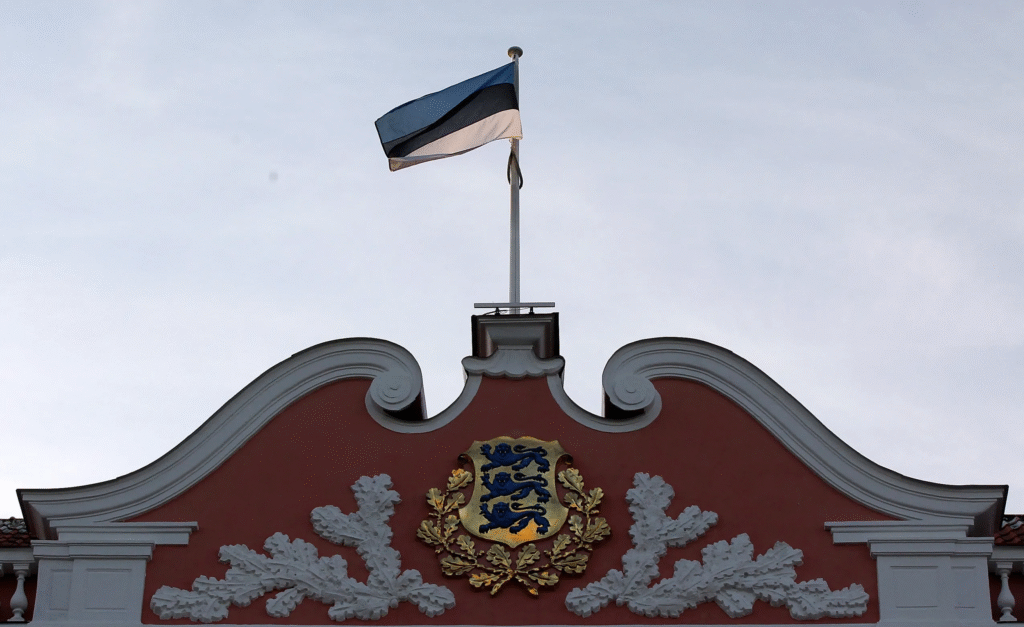

In a dramatic shift that lays bare the intensifying nationalism gripping the Baltic states, the Estonian parliament (Riigikogu) has passed a constitutional amendment revoking the right of non-EU citizens — including stateless persons — to vote in local elections. Backed by an overwhelming 93 votes out of 101, this decision will immediately disenfranchise over 11 percent of Estonia’s population and, by the next electoral cycle, a further 4.6 percent. In total, more than 15 percent of the country’s residents — many of them long-time contributors to Estonian society — will be stripped of a core democratic right.Framed as a necessary step to protect national sovereignty and prevent so-called “foreign interference,” this move amounts to little more than a cynical attack on the country’s sizable Russian-speaking minority.

This measure reflects not the safeguarding of democracy, but its calculated restriction, aimed at dividing the working class and consolidating a chauvinistic political narrative under the pretext of national security.

Constructing an “Internal Enemy”

Estonian officials have justified this decision by stoking fears that non-citizens, especially those of Russian and Belarusian descent, pose a threat to democratic institutions. Prime Minister Kristen Michal declared triumphantly: “The decisions in our local life won’t be made by the citizens of the aggressor states.” Such rhetoric not only criminalises entire communities based on national origin but effectively codifies collective punishment into law. President Alar Karis added a note of hollow reassurance, saying those stripped of their rights should not “feel excluded from social life” — a statement laced with contradiction.

How else should one interpret the revocation of voting rights, if not as exclusion? His words reflect the hypocrisy of a ruling class that seeks to placate the conscience of liberal observers while enacting measures rooted in xenophobic suspicion.

A Legacy of Statelessness

This disenfranchisement is not occurring in a vacuum. It continues a decades-long process of marginalisation rooted in the post-Soviet nation-building of Estonia and its Baltic neighbours. Unlike Lithuania, which granted citizenship to all residents in 1991, Estonia and Latvia adopted exclusionary policies, recognising only those who held citizenship prior to 1940 — and their descendants — as citizens. Others, often of Russian origin, were left stateless or forced to apply for naturalisation.

Today, over 160,000 non-EU residents live in Estonia. Among them, approximately 70,000 are Russian citizens and another 60,000 are stateless. Though many Russian speakers have acquired Estonian citizenship, tens of thousands have not — often due to bureaucratic hurdles, political resistance, or an unwillingness to renounce connections to their heritage. These individuals are now being punished under the chauvinistic logic that equates citizenship with loyalty and dissent with disloyalty.

Disguising Authoritarianism as Patriotism

The Estonian ruling class, along with its counterparts in Latvia and Lithuania, has long exploited ethnic divisions to fragment the working class. Since the collapse of the USSR, this has taken the form of language restrictions, attacks on Russian-medium education, and symbolic cultural provocations such as the removal of Soviet-era monuments. The new voting restrictions are simply the latest and most overt development in this strategy. Far from strengthening democracy, such measures undermine it. The ruling elite justifies them in the name of decolonisation and national identity, but their true function is to sow division and reinforce the ideological hegemony of a ruling class aligned with Western imperial interests. The real threat to Estonian democracy is not Russian-speaking pensioners casting ballots — it is the erosion of democratic norms under a state that increasingly defines belonging in narrow ethnic-nationalist terms.

Collateral Damage and Hypocrisy

Though the main target is clearly the Russian-speaking minority, this constitutional amendment impacts a wide range of people — including Ukrainians, Americans, and other non-EU nationals, many of whom have no ability to vote in any country at all. In their zeal to purge the ballot of “suspect” voters, Estonian lawmakers have disenfranchised citizens of NATO allies and war refugees alike.

Yet, little concern is expressed for these groups. Their exclusion is considered an acceptable cost in the pursuit of a chauvinistic political agenda. The silence on these broader consequences exposes the hypocrisy of a government that claims to be defending European democratic values while eroding them within its own borders.

A Smokescreen for Crisis

This amendment arrives amid growing social and economic hardship. Estonia is one of the most unequal countries in the Eurozone. Five percent of households control nearly half the nation’s wealth. The healthcare system is under severe strain, inflation has remained persistently high, and living costs are rising. Against this backdrop, the government has pledged to raise military spending to over five percent of GDP — to be financed not by taxing wealth, but by slashing public services and raising VAT on basic goods.

This is the real crisis facing Estonia — not the mythical danger posed by Russian-speaking retirees voting in municipal elections. The political establishment’s turn to anti-Russian chauvinism serves to obscure this reality. It allows the ruling class to deflect blame for economic inequality, austerity, and social decay by redirecting public anger toward an imagined “fifth column” within.

Divide and Rule

Estonia’s constitutional revision is not merely a legal change — it is a political signal. It demonstrates how, under the cover of nationalism and security, democratic rights can be curtailed to protect the interests of a narrow elite. It reflects a broader pattern across the Baltic region, where the language of resistance to Russian imperialism is cynically used to justify authoritarian measures, deepen inequality, and stoke divisions within the working class.

The disenfranchisement of non-citizens must be opposed not only as a violation of democratic principles but as part of a wider agenda to weaken class unity and entrench the power of a chauvinist ruling class. In Estonia, as elsewhere, the path to genuine democracy lies not in excluding others from political life, but in building a united struggle against inequality, xenophobia, and the capitalist system that breeds them both.