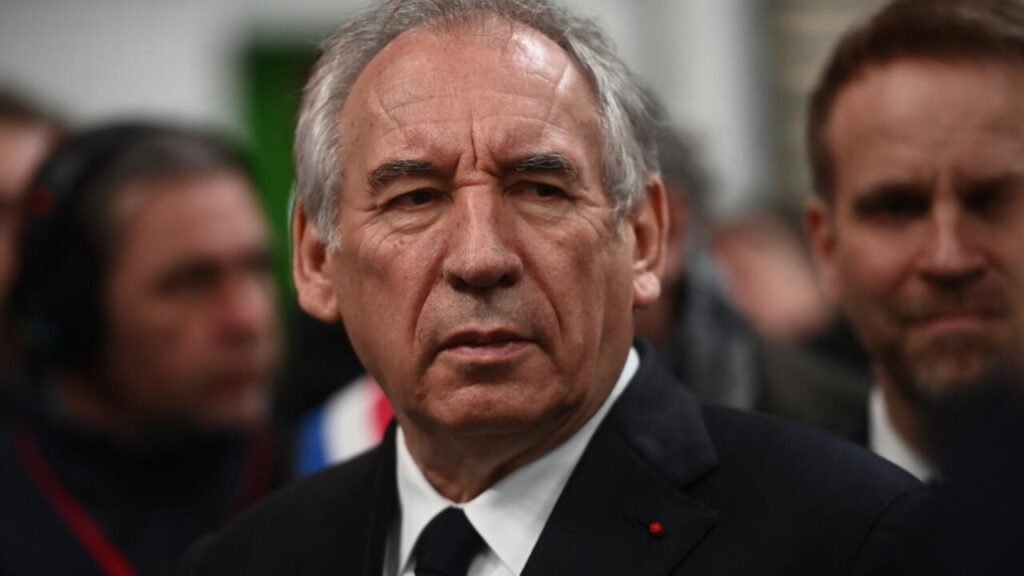

France is facing one of the most profound political and social crises of its recent history. What began as outrage over austerity policies and a collapsing government has now developed into a broader confrontation over the legitimacy of the current political order. With the resignation of Prime Minister François Bayrou following a failed vote of confidence, and widespread mobilization preparing to erupt across the country, the future of President Emmanuel Macron’s neoliberal agenda hangs in the balance.

Austerity from the Top Down

In mid-July, Bayrou presented his long-term budget proposals under the guise of fiscal urgency. Framing the national debt—amounting to 114 percent of GDP—and a budget deficit of 5.4 percent as existential threats, he proposed sweeping austerity measures. These included slashing unemployment benefits, freezing pensions, reducing public sector hiring, and curtailing social programs, while simultaneously increasing the military budget and offering no challenge to the privileges of the wealthy.

Far from being a departure from previous policy, this budget continued the core economic doctrine of Macron’s administration: a supply-side strategy prioritizing the demands of capital over the needs of the population.

The Bayrou plan made no mention of restoring the wealth tax or reversing corporate tax cuts, even though those policies contributed significantly to the growing public deficit. While the working class faced cuts to healthcare, education, and public services, France’s wealthiest citizens saw their fortunes double since 2017.

The political hypocrisy of these measures, especially when combined with the government’s refusal to respect the 2024 legislative election results—where the left-wing coalition Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) won a plurality—exacerbated public frustration. Macron’s consistent appointments of center-right figures to head governments against the popular mandate further deepened the democratic crisis. Bayrou’s resignation, while politically significant, does not mark the end of the neoliberal order—unless it is accompanied by a strong and unified popular response.

An Emerging Movement: Decentralized but Growing

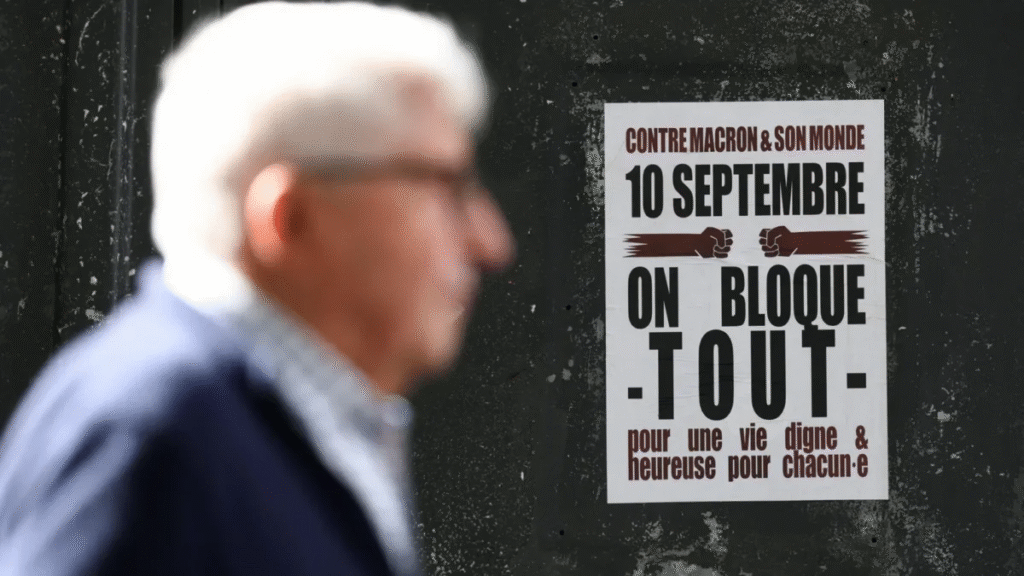

Over the summer, public discontent began to coalesce around the call to “block everything” on September 10. Although the movement’s initial organizers, a little-known group called “Les essentiels,” emerged with a mix of sovereigntist, conspiratorial, and anti-establishment rhetoric, the movement quickly evolved beyond its origins. Social media became a key driver of mobilization, spreading the call to action far beyond any single group or ideology.

While the mainstream media attempted to discredit the movement—labeling it incoherent, radical, or even Russian-sponsored—the popular response told a different story.

Petitions opposing environmentally and socially damaging policies, such as the reauthorization of the toxic pesticide acetamiprid, gained millions of signatures. On-the-ground organizing intensified through local assemblies, encrypted messaging groups, and homemade communications campaigns.

This new wave of activism includes a broad coalition: former gilets jaunes, union members, students, unemployed workers, retirees, and previously unaffiliated citizens. Their proposals range from symbolic actions like boycotts and mass withdrawals from banks, to more disruptive forms such as strikes, road blockades, and occupations. While ideologically diverse, their common grievances include the erosion of public services, economic injustice, and a political system seen as unresponsive and elitist.

The Left Joins the Fray—With Caution

A key difference between this emerging movement and previous cycles of unrest is the early engagement of left-wing political forces. France Insoumise, followed by other parties including the Greens, Communists, and even the Parti Socialiste, announced their support for the September 10 mobilization. Most emphasized the importance of maintaining the movement’s independence, while also encouraging active participation.

Trade unions were initially hesitant. However, under pressure from their rank-and-file, major confederations such as the CGT and Solidaires issued calls to strike on September 10. More moderate federations like the CFDT have kept their distance, though all major union groups are aligned for a broader mobilization on September 18. Civil society organizations—feminist groups, climate activists, and tax justice associations—have also lent their voices to the growing chorus of opposition.

The far right, notably the Rassemblement National led by Marine Le Pen, has chosen not to participate officially. However, as with the early Yellow Vest protests, its supporters are present on the ground. This ideological proximity poses a risk of co-optation or confusion, which progressive forces must confront with political clarity and grassroots organization.

Bayrou’s Fall and the Political Scenarios Ahead

Bayrou’s decision to call a confidence vote just days before the planned demonstrations was likely an attempt to defuse momentum. The tactic failed: the National Assembly voted overwhelmingly against him, forcing his resignation. Now, Macron faces a set of difficult choices.

He could attempt to appoint another prime minister from the pro-Macron coalition, possibly Sebastien Lecornu. But any government lacking parliamentary legitimacy would face the same crisis of governance. Alternatively, he might pursue a coalition stretching from center-right Républicains to the Parti Socialiste, though this would risk alienating the broader left and triggering internal fracture.

A second option would be to dissolve the National Assembly and call new elections. Macron has previously ruled this out—but has shown little regard for consistency in practice. Such a move could serve as a delaying tactic, absorbing the energy of protest into electoral procedures and attempting to shore up legitimacy through the ballot box.

A third, less likely but increasingly discussed outcome is Macron’s own resignation. A recent poll shows that 67 percent of French citizens support this path, though France’s institutional system offers limited mechanisms for presidential removal. France Insoumise has floated a motion of impeachment, but such efforts are procedurally difficult and historically unprecedented under the Fifth Republic.

What Comes Next?

Bayrou’s exit changes the political landscape but does not resolve the deeper systemic crisis. A return to Macron’s style of governance—with technocratic elites imposing austerity through executive power—would only prolong the unrest. New elections offer little promise if the political establishment continues to sideline democratic mandates.

What is needed is a new political configuration—grounded in social mobilization, accountable institutions, and a break with the economic orthodoxy that has failed the majority. The left must remain united around this vision. Divisions, especially attempts to isolate France Insoumise from coalition-building, would only weaken its capacity to offer an alternative to both neoliberalism and the far right.

The coming weeks will be decisive. If the September 10 movement expands and deepens—if workers, students, and communities come together under a shared project—then a real rupture with the current order is possible. In that case, the fall of Bayrou may not be the end of the crisis, but the beginning of genuine transformation.