Portugal’s Rightward Turn: Collapse of the Left and the Rise of Reaction

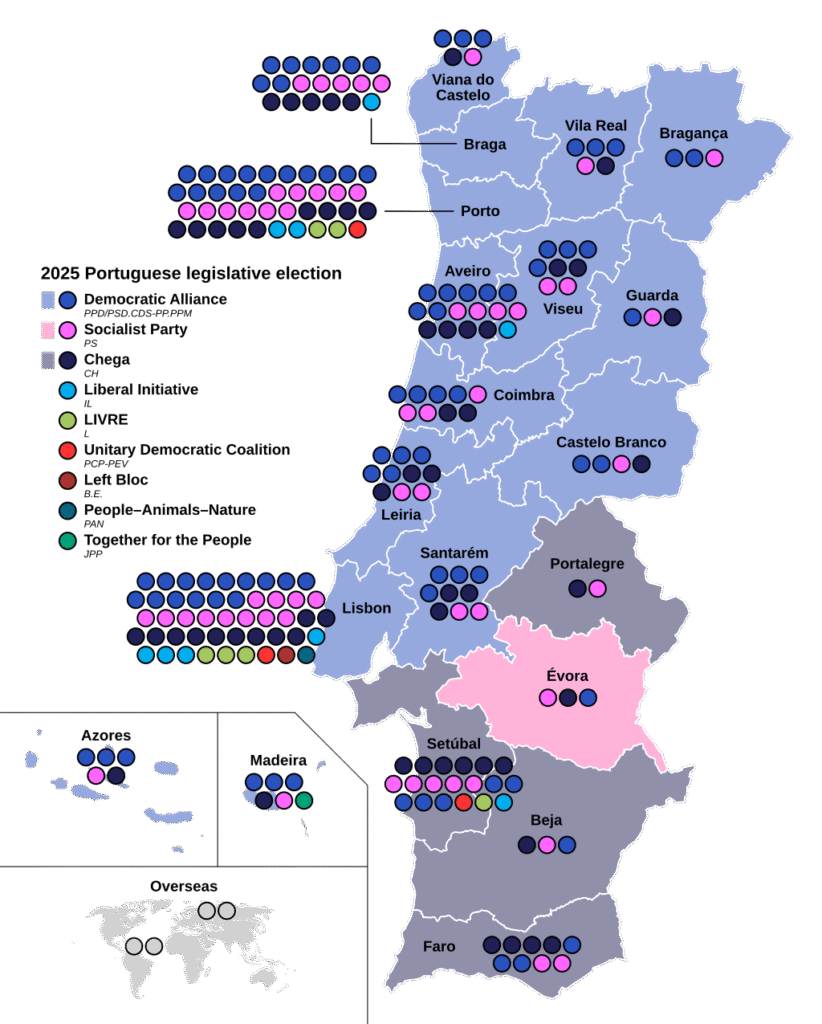

The Portuguese parliamentary elections held on May 18 marked the end of a long-standing political balance in the country. The conservative Democratic Alliance (AD) emerged as the largest political force, securing 32% of the vote. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party (PS) suffered a historic blow, finishing in a statistical tie with the far-right Chega party, each capturing around 23% of the vote. The radical left, once influential, was decisively routed: the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Left Bloc (BE), combined, managed just 5%.

This outcome signals a dramatic rupture in what was once dubbed the “Portuguese exception” — the idea that Portugal had avoided the far-right surges seen across Europe. That illusion has now been shattered. Portugal is no longer the outlier but has joined the continental trend of polarization, instability, and a weakened left.

From Stability to Crisis: The Fall of Costa

The political unraveling began in November 2023, when Prime Minister António Costa, leader of the PS, resigned amid corruption allegations. Though the ensuing investigation failed to substantiate the charges — raising questions of judicial overreach or even lawfare — the damage was done. The resignation marked the end of eight years of Socialist-led governance, during which Portugal was often held up as a progressive model alongside Spain.

In the span of three years, Portugal has held three national elections — each reflecting deeper instability and declining trust in traditional institutions. As the Left has lost ground, Chega has risen rapidly, evolving from a marginal party founded in 2019 to the central player in a new political reality. In the words of Chega’s leader, André Ventura, “bipartisanship is over.” For once, the far right is not exaggerating.

The Normalisation of the Far Right

Chega’s success stems not merely from public anger at corruption but from a well-calculated narrative that fuses anti-elitism, anti-immigration rhetoric, and authoritarian solutions to social crises. Despite numerous scandals involving its own members — including cases of drunk driving, theft, and even child exploitation — the party has managed to present itself as a clean, insurgent alternative to a discredited political class. The collapse of PS support has enabled Chega to expand its base. Surveys indicate that former Socialist voters helped fuel the party’s rise — a dangerous trend echoed across Europe, where parts of the working class, abandoned by the left, gravitate toward reactionary nationalism. Unlike Spain, where the far-right Vox draws primarily from conservative voters, Chega has begun winning over the very constituencies once loyal to the left. The governing conservatives themselves have inadvertently legitimised Chega’s platform. In December 2024, Lisbon witnessed racially motivated police raids, widely perceived as the state conceding to Chega’s anti-immigrant agenda.

Despite public protests, these raids marked a pivotal moment: the xenophobic language of the far right had entered the mainstream.

The Collapse of the Left

The most dramatic failure of the election belongs to the Left. The Socialist Party lost 350,000 votes compared to the previous election — its third-worst result since Portugal’s democratic restoration in 1974. Party leader Pedro Nuno Santos promptly resigned.

This defeat is especially bitter considering the PS’s historical legacy. Until the 1980s, Marxism was officially recognised as the party’s guiding ideology. It was instrumental in building democratic institutions following the Carnation Revolution that overthrew the Salazar dictatorship. That legacy has now been hollowed out.

The radical left fared even worse. From 2015 to 2023, the PCP and the Left Bloc had played key roles in supporting Socialist-led governments through parliamentary pacts. Today, they are almost irrelevant: together, they hold just five seats in parliament. Livre — a small party ideologically situated between the PS and the radical left — showed modest improvement with 4.2% of the vote, but nowhere near enough to counterbalance the broader defeat.

Geographically, the picture is equally stark. The conservative AD now dominates the North and Center of Portugal. In the South, once a Socialist stronghold, Chega has become a serious competitor, outperforming the PS in 121 out of 308 municipalities and winning four of Portugal’s twenty districts. By contrast, the Socialists led in only one district. With local elections expected in autumn, the risk of Chega translating votes into institutional power is very real.

Institutional Constraints and Dangerous Prospects

As Portugal is a semi-presidential republic, the appointment of the next prime minister lies with the conservative President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. The likely outcome is a minority government led by Luís Montenegro of AD, as forming a coalition with Chega would be politically toxic — at least for now.

Nonetheless, Ventura and Chega will continue to posture as anti-system crusaders. Their exclusion from formal power may benefit them in the short term by reinforcing their outsider image. Any future collaboration between AD and Chega could prove risky, especially in a country where the shadow of Salazar’s dictatorship still shapes political consciousness.

Europe’s Broader Rightward Drift

Portugal’s election confirms what is now a well-established pattern across much of Europe: the erosion of the centre-left and the institutionalisation of the far right. Chega’s rise mirrors developments in France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden, where anti-immigrant, ultra-nationalist parties have entered parliaments and, in some cases, governments.

Only a few exceptions remain. Spain’s fragile PSOE–Sumar coalition has held the far right at bay, for now, and France’s La France Insoumise continues to maintain a strong left presence. But the continental tide is clear: neoliberal centrism is in retreat, and social democracy has failed to offer a compelling alternative to nationalist reaction.

A Political Order in Decline

Portugal’s May 18 election was not an isolated shift — it was a rupture. The steady erosion of the Left, the fragmentation of the political centre, and the mainstreaming of far-right narratives have created a new political reality.

If the Left is to recover, it cannot rely on nostalgia or technocratic governance. It must offer a bold, class-conscious, and democratic alternative — one that speaks to the material concerns of workers, the unemployed, the young, and immigrants. Until then, parties like Chega will continue to occupy the vacuum, offering false answers to real crises.

What has collapsed is not only a political coalition but the credibility of a political order. The next battle will not only be electoral — it will be ideological and social.