Among the many slogans that capitalists and their defenders use, “freedom” is perhaps the most frequently invoked and the least understood. For proponents of free-market capitalism, freedom means the unrestricted ability of individuals to pursue their economic interests, believing that such liberty will lead to the prosperity of society as a whole. This notion, epitomized by Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom, remains central to capitalist ideology. However, a closer examination reveals that the freedom celebrated by capitalism is deeply contradictory and has always been intertwined with coercion and exploitation. The birth of capitalism, far from being a story of individual liberty, is rooted in a history of dispossession, slavery, and the subjugation of entire peoples.

The Decline of Feudalism and the Rise of a New Order

The seeds of capitalism were sown amidst the crumbling ruins of feudal Europe. Contrary to popular belief, the initial blows against feudalism were not struck by the burgeoning merchant class or moneylenders, but by the oppressed serfs—the semi-slaves who labored for the feudal lords and the Church. These serfs, bound to the land and compelled to perform unpaid labor, constituted the foundation of the medieval economy. Their struggle for liberation laid the groundwork for the emergence of a new social order.

In medieval Europe, serfs were considered part of their lord’s property, bound to the land they worked. The only means of escape from this oppressive system was to flee to the towns, where a legal principle known as “Stadtluft macht frei” (“city air makes you free”) granted freedom to any escaped serf who managed to live in a town for a year and a day. This principle, however, did not arise from the benevolence of the rulers but from a long and bitter struggle between the serfs and their feudal overlords. It was this persistent fight for freedom that contributed to the growth of independent towns, which became hubs of trade and early capitalist enterprise.

The Transformation of European Society

The rise of these towns and the expansion of trade began to undermine the feudal system. By the 14th century, feudalism was already in decline across much of Europe. The Black Death, which decimated the population, paradoxically strengthened the bargaining position of the surviving serfs. As labor became scarce, wages rose, and many peasants were able to negotiate better terms with their lords. However, the ruling class responded with harsh measures to maintain their control, leading to uprisings such as the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Although brutally suppressed, these revolts marked the beginning of the end for serfdom in Western Europe.

The decline of feudalism was accompanied by the rise of a new class—the bourgeoisie. This class, initially composed of town dwellers, merchants, and artisans, began to assert its influence over the economic and political life of Europe. As the feudal order crumbled, the bourgeoisie seized the opportunity to reshape society in its own image, promoting the growth of trade, the expansion of markets, and the accumulation of capital. This transformation laid the groundwork for the capitalist mode of production, where labor and commodities became objects of exchange.

The World Market and the Expansion of Capital

The growth of the world market was a crucial factor in the development of capitalism. The increasing demand for commodities and the expansion of trade routes across Europe and beyond fueled the accumulation of wealth. By the 15th century, European merchants were engaged in a complex web of trade that spanned the Mediterranean and reached as far as Asia. The demand for precious metals, particularly silver, to facilitate this trade led to the infamous “gold lust” that drove European explorers to the New World.

The so-called “Age of Discovery” was, in reality, an era of brutal conquest and exploitation. The Spanish conquest of the Americas, driven by the pursuit of gold and silver, resulted in the destruction of entire civilizations and the enslavement of millions. The extraction of wealth from the New World through forced labor and the plunder of resources was a foundational moment in the development of global capitalism. The Atlantic slave trade, which forcibly transported millions of Africans to the Americas to work on plantations, was another integral part of this emerging world market.

The Birth of Capitalism: Enclosures and the Agrarian Revolution

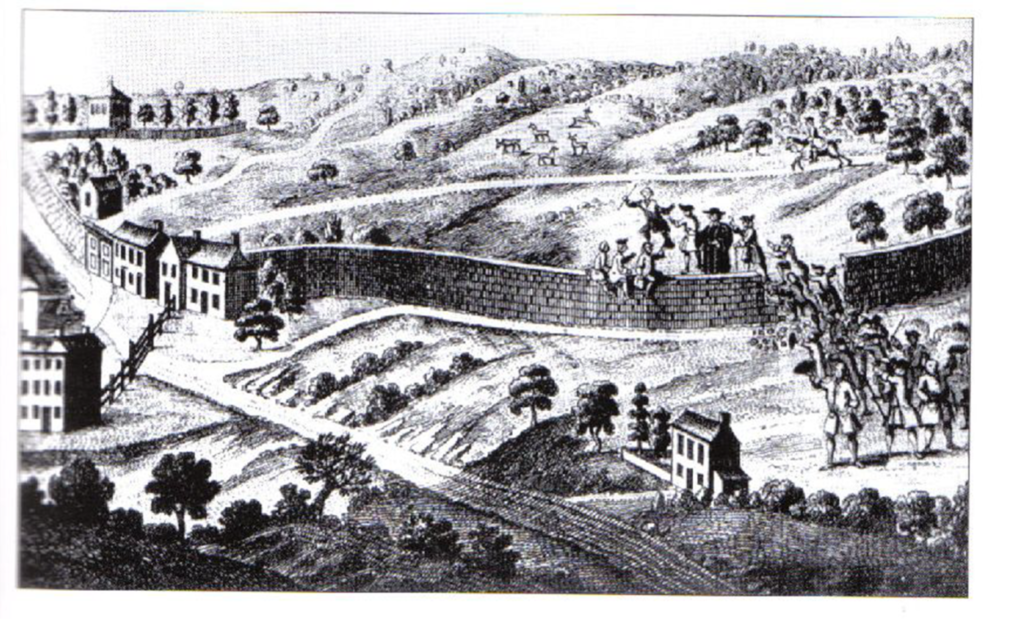

While the conquests abroad were fueling the growth of the world market, a parallel process of transformation was occurring within Europe itself. The decline of feudalism gave rise to the agrarian revolution, which transformed the rural landscape and laid the foundation for the industrial revolution. The enclosure movement in England, which began in the late 15th century and continued into the 18th century, was a key aspect of this transformation.

Enclosure involved the consolidation of common lands into privately owned plots, which were often used for more profitable agricultural practices, such as sheep farming. This process, driven by the desire of landowners to increase their profits, led to the dispossession of thousands of peasants. Stripped of their land and livelihoods, these displaced peasants were forced to migrate to the growing towns and cities, where they formed a new class of wage laborers—the proletariat.

This “primitive accumulation,” as Karl Marx described it, was a violent and coercive process that created the conditions necessary for the development of capitalism. By forcibly separating the producers from the means of production, the enclosures transformed land into a commodity and created a mass of landless workers who were dependent on wage labor for their survival. This new class of workers became the foundation of the emerging capitalist economy, which was based on the exploitation of labor for profit.

Slavery and the Global Expansion of Capital

The birth of capitalism was not confined to Europe. The global expansion of capital was marked by the brutal exploitation of non-European peoples through slavery and colonialism. The Atlantic slave trade, which transported millions of Africans to the Americas, was one of the most horrific chapters in this history. The profits generated from the slave trade and the labor of enslaved people on plantations were integral to the development of European capitalism.

The colonial conquest of the Americas and the exploitation of its indigenous peoples were also central to the accumulation of capital. The wealth extracted from the colonies was used to finance the development of industry in Europe and to fuel the growth of the global market. The transformation of entire continents into sources of raw materials and markets for European goods was a fundamental aspect of the capitalist system.

The relationship between freedom and slavery, which lies at the heart of the capitalist system, was starkly evident in the colonies. While the bourgeoisie in Europe celebrated their own “freedom” as property owners and entrepreneurs, they simultaneously built an empire on the backs of enslaved Africans and dispossessed indigenous peoples. The wealth that flowed into Europe from the colonies financed the industrial revolution and laid the foundations for the modern capitalist world.

The Role of the State in the Development of Capitalism

The development of capitalism was not the result of individual enterprise alone. The state played a crucial role in facilitating the accumulation of capital through coercive means. The process of enclosure in England, for example, was enforced by a series of acts of Parliament that legalized the privatization of common lands. Similarly, the colonial conquests were backed by state power, with European armies and navies enforcing the subjugation of entire peoples.

The state also played a role in creating the conditions for capitalist accumulation within Europe. The suppression of guilds and other restrictions on trade, the establishment of national markets, and the regulation of labor were all part of the process of creating a unified capitalist economy. The creation of the Bank of England and the establishment of the national debt were key financial innovations that facilitated the growth of the capitalist system.

The development of capitalism, therefore, was not a smooth or peaceful process. It was marked by violence, coercion, and the systematic expropriation of resources and labor. The state, far from being a neutral arbiter, was an active participant in this process, using its power to enforce the conditions necessary for the accumulation of capital.

The Birth of the Working Class and the Industrial Revolution

The transformation of the rural population into a class of wage laborers laid the groundwork for the industrial revolution. As capital accumulated, it was invested in the development of new technologies and the establishment of factories. The industrial revolution, which began in England in the late 18th century, marked a fundamental shift in the organization of production and the nature of work.

The new industrial system was based on the exploitation of labor on a massive scale. The working class, which had been created through the process of enclosure and dispossession, was now subjected to the harsh discipline of factory labor. The conditions of work in the early factories were brutal, with long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions. Child labor was common, and workers had little or no protection against the arbitrary power of their employers.

The industrial revolution transformed not only the economy but also the social and political landscape of Europe. The concentration of workers in the new industrial towns and cities created the conditions for the emergence of a powerful labor movement. The struggles of the working class for better wages, shorter hours, and the right to organize laid the foundations for the modern labor movement and the development of socialist and communist ideologies.

The Contradictions of Capitalist “Freedom”

The freedom celebrated by capitalist ideology has always been a highly selective and contradictory concept. The “freedom” of the capitalist to exploit labor and accumulate wealth has been achieved through the unfreedom of the majority. The birth of capitalism was not a story of liberty and individual enterprise but of coercion, exploitation, and the systematic oppression of entire classes and peoples.

The contradictions of capitalist freedom are evident in the relationship between the bourgeoisie and the working class. While the bourgeoisie celebrates its own freedom to own property and accumulate wealth, it denies the working class the freedom to control the conditions of its own labor. The worker is free only in the sense that they are free to sell their labor power to the capitalist, a freedom that is little more than the freedom to choose between exploitation and starvation.

The contradictions of capitalist freedom are also evident in the relationship between the capitalist core and the colonial periphery. The freedom of the European bourgeoisie was built on the unfreedom of enslaved Africans and colonized peoples. The wealth that financed the development of capitalism in Europe was extracted through the exploitation and oppression of non-European peoples, a legacy that continues to shape global inequalities to this day.

The Legacy of Capitalist Freedom and the Struggle for Emancipation

The history of capitalism is a history of contradictions. The freedom it celebrates has always been inseparable from the unfreedom it imposes. The birth of capitalism was marked by the dispossession of peasants in Europe, the enslavement of Africans, and the conquest and exploitation of entire continents. The development of the capitalist system was driven not by the spirit of liberty but by the relentless pursuit of profit, a pursuit that has always been accompanied by violence and coercion.

Today, the contradictions of capitalist freedom are as evident as ever. The global inequalities that are the legacy of colonialism and slavery continue to shape the world we live in. The exploitation of labor and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few are the defining features of the modern capitalist system. The freedom celebrated by capitalism remains, as always, a freedom for the few, built on the unfreedom of the many.

The struggle for genuine freedom requires more than the reform of the existing system. It requires the transformation of the social and economic relations that underlie the capitalist system. It requires the abolition of the conditions of exploitation and oppression that have been the foundation of capitalism from its inception. It requires the building of a society based on equality, solidarity, and the common ownership of the means of production—a society in which freedom is not a privilege for the few but a right for all.