After more than a decade of devastating conflict, Syria finds itself in a fragile phase of political transition. At the center of this shift stands interim president Ahmed al-Sharaa, who, in September, became the first Syrian head of state to address the United Nations General Assembly in over sixty years. This appearance projected the image of a nation turning a page. Yet beneath the surface, the country’s internal dynamics suggest a far more complex and troubled reality.

A Managed Electoral Process

On October 5, Syria held its first elections since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. These elections were meant to symbolize a new chapter for the war-torn country. However, in practice, they were carefully stage-managed. The process was tightly controlled by the new authorities, with political parties barred from participating and only unaffiliated individuals permitted to run. Voter participation was alarmingly limited: only a few thousand Syrians were registered, while millions inside the country — and over six million abroad — remained disconnected from the process. Rather than a celebration of democracy, the elections underscored the dominance of the new regime and its reluctance to empower the broader population.

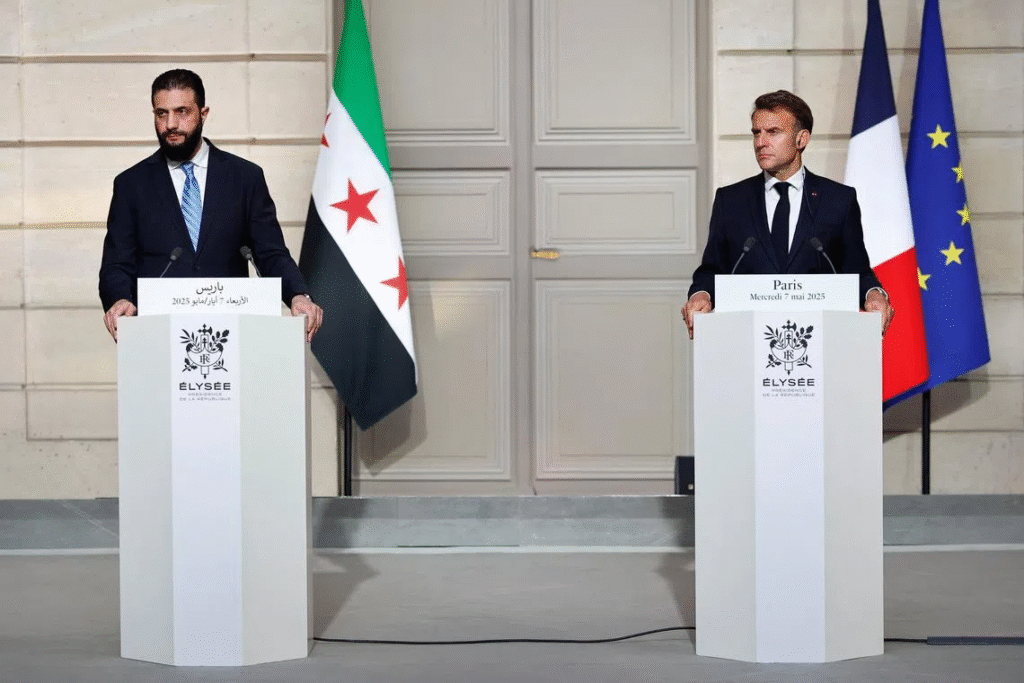

International Legitimacy, Domestic Uncertainty

The Sharaa administration has prioritized consolidating authority both within Syria and on the world stage. Since assuming power, it has pursued normalization with international actors once hostile to Damascus. Turkey has extended full diplomatic recognition. Sanctions imposed by the United States, European Union, and Japan have been lifted, opening avenues for foreign investment. Agreements with corporations from Qatar, China, the UAE, and Turkey—focused on infrastructure and energy—have been signed, amounting to billions in pledged investments.

Notably, the removal of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) from Western terror watchlists signaled a major shift. While HTS, a former affiliate of al-Qaeda, remains central to the new power structure, it has strategically rebranded to project a more pragmatic, nationalist image. These developments reflect a broader recalibration by international powers—trading democratic ideals for a promise of stability in post-war Syria.

Internal Fragmentation and Sectarian Tensions

Despite diplomatic gains, Syria remains deeply fractured. July saw violent clashes in the southern governorate of Sweida, a predominantly Druze region, where tensions flared between local militias, bedouin tribal groups, and government forces. Simultaneously, unrest continued in the Alawi-dominated coastal areas and Kurdish-majority northeast. The government’s intervention in Sweida aimed to reassert control but ended up escalating violence.

Of particular concern are the ongoing negotiations with Israel in Baku concerning the Golan Heights—Syrian territory under Israeli occupation since 1967. While the talks are framed as diplomatic overtures, many Syrians view them as capitulations. Internal dissent has also grown over Israeli airstrikes targeting Syrian military positions, especially amid speculation that Israel may be backing Druze factions hostile to the central government.

Fragile Institutions, Militarized Society

After Assad’s fall, Syria’s state institutions—already hollowed out by war, corruption, and mismanagement—collapsed almost entirely. In this void, numerous armed groups emerged. Some were opportunistic—springing from abandoned military depots—while others were organized along sectarian or ethnic lines. HTS loyalists control portions of the northwest; Kurdish-Arab coalitions dominate parts of the northeast. In Sweida and elsewhere, local militias operate autonomously, resisting government authority even while loosely coordinating on security matters.

The Sharaa administration has struggled to unify the country’s fragmented armed landscape under a centralized command. While the new Ministry of Defense attempts to integrate these groups, competing allegiances and tribal loyalties remain potent obstacles.

Living Conditions and Public Discontent

A year into the new administration, the socioeconomic conditions of ordinary Syrians remain dire. More than 90% of the population lives in poverty, and over two-thirds require humanitarian aid. Prices of basic goods continue to rise, while public services remain in disrepair. Amid widespread unemployment and underemployment, protests over wages and living conditions have erupted sporadically—especially among public sector workers like teachers—though they are often suppressed through intimidation or worse.

The few attempts at labor organizing have been crushed. Early strikes by state employees demanding better wages and working conditions vanished after government crackdowns in Latakia and Tartus. Unions and independent political organizations have been dissolved under the guise of national unity, and many civil society actors have been forced into silence or exile.

Sectarian Violence as Strategy

Though the government presents itself as a unifying force, its actions tell another story. Sectarian tensions are not just byproducts of conflict; they are frequently used as instruments of governance. In Sweida, the government’s alliance with certain bedouin groups led to brutal fighting with Druze militias. Kidnappings, massacres, and airstrikes followed, displacing tens of thousands. Humanitarian organizations report over 800 civilian deaths and hundreds more wounded since July alone.

The government has blamed outside actors, particularly ISIS, for attacks on minority communities—such as the June assault on Christians in the Damascus suburbs—but many Syrians view these claims with skepticism. In several cases, lesser-known militias with ambiguous affiliations have claimed responsibility, raising concerns about the state’s ability or willingness to protect all segments of society equally.

The reality is that sectarian narratives are being used both to justify repression and to divide opposition. The government exploits Sunni grievances against the Assad-era regime while simultaneously vilifying other ethnic and religious minorities as scapegoats for the nation’s instability. This tactic effectively fragments opposition, preventing the emergence of a broad-based coalition for change.

Concentration of Power and Constitutional Manipulation

In March, a new interim constitution was adopted. Though it nominally enshrines freedoms of speech, religion, and political association, it simultaneously grants sweeping powers to the president. Al-Sharaa now controls judicial appointments, one-third of the legislature, and can unilaterally declare states of emergency. These changes undermine any potential for genuine checks and balances. Internationally, the government has made notable gains. U.S. sanctions—particularly the Caesar Act—have been rescinded, and Syria has rejoined the SWIFT banking system. Yet these developments benefit the political elite far more than the average Syrian. Meanwhile, Sharaa’s diplomatic overtures to Israel, presented as pragmatic steps toward normalization, are seen by many as betrayals of long-held national principles.

A Controlled Pluralism

While fears of a full-blown Islamic state have not materialized, the new regime operates as a hybrid: centralizing power through authoritarian means while offering limited concessions to local leaders and religious figures. This “controlled pluralism” allows the administration to co-opt potential rivals while maintaining the appearance of inclusivity.

However, the narrowing space for political expression, combined with persistent violence and sectarian manipulation, casts doubt on the sincerity of this transitional period. For now, the new Syrian state remains less a break from the Assad regime and more a reconfiguration—retaining many of the same repressive dynamics under a different banner.

Stability or Stagnation?

Syria today is a country suspended between recovery and repression. Though major combat operations have ceased, violence continues in more insidious forms—through institutional marginalization, economic dispossession, and identity-based targeting.

Ahmed al-Sharaa’s administration has effectively rebranded Syria’s ruling structure, trading open dictatorship for managed authoritarianism. Western governments and regional powers appear willing to support this arrangement in exchange for a semblance of stability. But beneath this surface calm lies a fractured society, still grappling with the legacies of war, inequality, and unaccountable governance.

Without meaningful reforms, power-sharing mechanisms, and an inclusive political process, Syria’s so-called transition risks ossifying into yet another phase of authoritarian rule—one propped up by foreign investment and fragile alliances, but devoid of legitimacy in the eyes of its people.