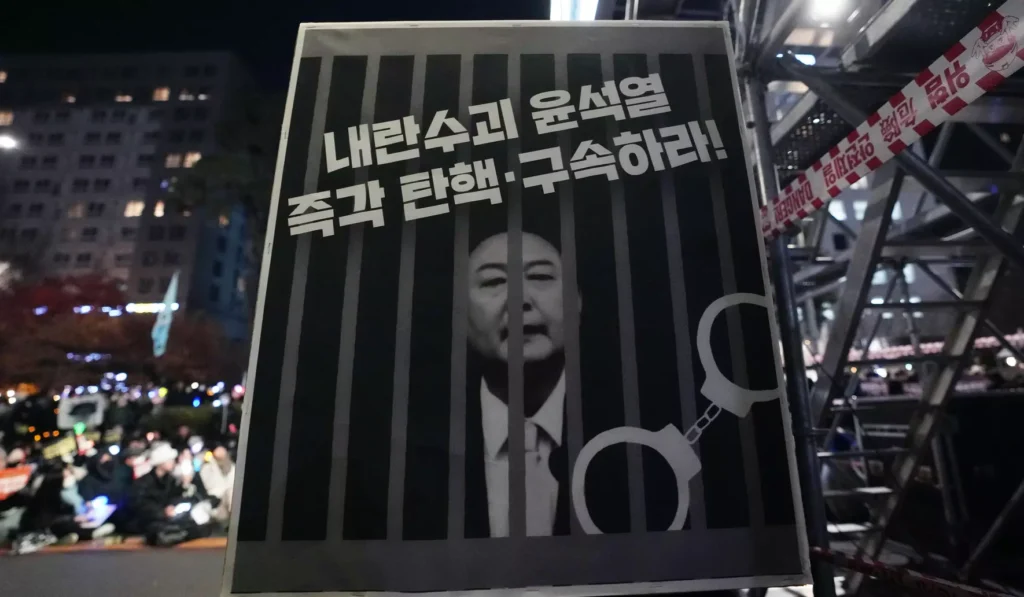

The recent judicial reckoning in Seoul marks a watershed moment not only for South Korea but for the global left. On February 19, 2026, a Seoul court sentenced former conservative President Yoon Suk-yeol to life imprisonment for insurrection. This monumental verdict arrived 443 days after Yoon’s desperate and abrupt self-coup attempt on December 3, 2024, an effort to subvert the constitutional order that crumbled within a mere six hours following unanimous legislative rejection and massive, spontaneous public protests. As the sole advanced capitalist democracy to recently neutralize a far-right authoritarian surge through a potent mixture of mass mobilization and electoral action, South Korea offers critical lessons. However, a closer examination reveals that justice remains fundamentally incomplete, heavily entangled in the systemic political and class tensions that precipitated Yoon’s power grab in the first place.

Judicial Ambiguity and the Far-Right Resurgence

The sentencing, delivered by presiding judge Ji Gwi-yeon, was fraught with ideological concessions that threaten to embolden the very forces it sought to punish. Judge Ji—who had previously permitted Yoon a brief release on a technicality in July 2025—oscillated between upholding the rule of law and deferring to the powers of the executive branch. Strikingly, the judge stopped short of classifying Yoon’s actual declaration of martial law as an act of insurrection, implicitly validating the deposed leader’s justification. Yoon had cynically defended his martial law decree (which he termed gyemongryung, combining the Korean words for martial law and enlightenment) as an “enlightening” measure necessary to combat alleged leftist threats and Chinese interference in domestic elections.

Coupled with a shrewd plea of sheer incompetence—famously asking the court, “How could a fool like me carry out a coup?”—Yoon managed to evade the death penalty, the maximum punishment for his crimes (though South Korea has not executed anyone since the late 1990s). Ultimately, Judge Ji convicted Yoon strictly for deploying special forces to the National Assembly and the National Election Commission to arrest his opponents. Yet, by utilizing an old English proverb, “Do not steal a candle to read the Bible,” the judge appeared to sympathize with Yoon’s underlying, reactionary motives, thereby handing a potent ideological weapon to the far right. Following the verdict, Jang Dong-hyuk, a leader of Yoon’s People’s Power Party (PPP)—which still controls roughly a third of the National Assembly—seized upon this judicial equivocation to insist upon Yoon’s innocence, resisting internal calls to purge the former president’s legacy.

The Imperialist Nexus and Youth Radicalization

Yoon’s putsch was not an isolated anomaly, but the eruption of decades-long friction among the far right, liberals, and the working-class left. The immediate wave of far-right counterprotests following the coup attempt underscores a dangerous demographic and ideological shift: a rising tide of pro-United States, anti-China ultraconservatism among South Koreans in their twenties. Facing an increasingly hostile capitalist landscape marked by severe housing shortages, a tightened job market, and the total collapse of upward social mobility, many young people have gravitated toward reactionary ideologies. This generational schism is stark; the youth view themselves in opposition to the left-leaning, pro-democracy generation of their parents (who fought against the dictatorships of the 1970s and 80s) because that older cohort has successfully monopolized the nation’s economic and political wealth.

This reactive, anti-China hostility is aggressively cultivated by YouTube influencers and activist Christian ministers, and crucially, it is now being actively subsidized and guided by MAGA and Christian nationalist networks based in the United States. Unlike the Cold War era, where US-South Korean ties were strictly military, the American civilian far right is directly exporting its ideological framework to Seoul. The late US far-right operative Charlie Kirk made Seoul his final overseas destination before his assassination in September 2025, delivering the keynote address for Build Up Korea, an organizational clone of Turning Point USA. Following his death, radicalized youths even erected a makeshift altar for Kirk in Seoul. Groups like Build Up Korea and Free University now serve as foot soldiers for “Yoon Again” campaigns, organizing campus debates modeled on Kirk’s aggressive rhetorical style.

Furthermore, these South Korean ultraconservatives boast direct lines to the Trump administration, notably through Vice President J.D. Vance, a staunch advocate of Christian nationalism. Vance personally intervened in January to express concern over the detention of Son Hyun-bo, a far-right Presbyterian minister jailed for violating electoral regulations. Following the waiving of his six-month sentence in February, Son publicly boasted that his two adult sons had been hosted at the White House twice while he awaited trial.

The Liberal Illusion: Lee Jae-myung and the KOSPI Bubble

On the other side of the political spectrum, the liberal Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) and its leader, Lee Jae-myung, reaped the immediate political dividends of Yoon’s collapse. Despite winning the snap presidential election in May 2025, Lee failed to secure an absolute majority, reflecting both the entrenched strength of the far right and persistent public anxiety regarding his own corruption scandals. Nevertheless, six months into his tenure, Lee enjoys a 60 percent approval rating from Gallup Korea, a staggering figure achieved without enacting any meaningful economic or structural reforms.

Lee’s popularity rests precariously on the illusion of capitalist stability and a speculative stock market boom. His administration’s primary political asset is the explosive growth of the KOSPI composite index, which recently hit an all-time high. Fulfilling a core campaign pledge in a nation where a quarter of adults trade stocks, Lee has tied his political fate to the market. However, this economic narrative masks severe structural unevenness; the KOSPI’s surge is overwhelmingly driven by a global AI boom that has artificially inflated the value of two semiconductor monopolies, Samsung and SK Hynix, which alone constitute roughly 40 percent of the index. This hyper-concentration presents extreme systemic risks, vastly exceeding even the top-heavy nature of the US S&P 500.

The Betrayal of Labor and the Necessity of an Independent Left

While Lee hides behind soaring stock tickers—metrics that offer absolutely no material gains for the broader working class—the DPK is fracturing. An internal power struggle is raging between the party’s left-nationalist old guard from the 1980s student movement and a rising faction of liberal professionals, newly wealthy tech entrepreneurs, and financial elites closely aligned with Lee. This new liberal cadre treats the DPK as a modern alternative to the old-fashioned, authoritarian industrialist model of the PPP.

Consequently, the DPK has systematically abandoned its promises to the working class. The Lee government has conveniently stalled on revising South Korean labor laws to guarantee essential protections for platform workers and freelancers. Regardless of which DPK faction emerges victorious, the party is firmly on a trajectory to completely jettison its pro-labor rhetoric, despite continuing to rely on the political support of major unions like the independent Korean Confederation of Trade Unions.

The rapid defeat of Yoon’s coup was an undeniably inspiring victory for the masses. Yet, the current trajectory of South Korea serves as a stark warning. The experience decisively proves that without a mobilized, independent left, any popular democratic gains are destined to be co-opted, eroded, or misdirected by the liberal capitalist establishment long before the existential threat of the far right is truly eradicated.