South Africa is currently grappling with one of the most severe energy crises in its history. Daily life has been disrupted by rolling blackouts, referred to locally as “load shedding,” with the country’s energy supplier, Eskom, struggling to maintain the power supply. These blackouts have significantly intensified since September 2022, with homes, businesses, and factories experiencing power cuts of up to eight hours per day. The scale of the crisis is unprecedented, as South Africa endured more power cuts in 2022 than in any other year since the crisis began 15 years ago.

The consequences for the economy are dire. The ongoing power outages have shaved two percentage points off the country’s economic output, exacerbating unemployment and pushing more people into poverty. Furthermore, the daily routines of citizens have been upended, with food spoilage and the frequent closure of businesses becoming common occurrences.

In his State of the Nation Address in February 2023, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared the electricity crisis a national state of disaster under the Disaster Management Act, granting the government additional powers to tackle the situation. Ramaphosa also announced a cabinet reshuffle, creating a new Ministry of Electricity. However, these moves have been criticized as last-ditch efforts to manage a crisis that has its roots in mismanagement and systemic failings over the past two decades.

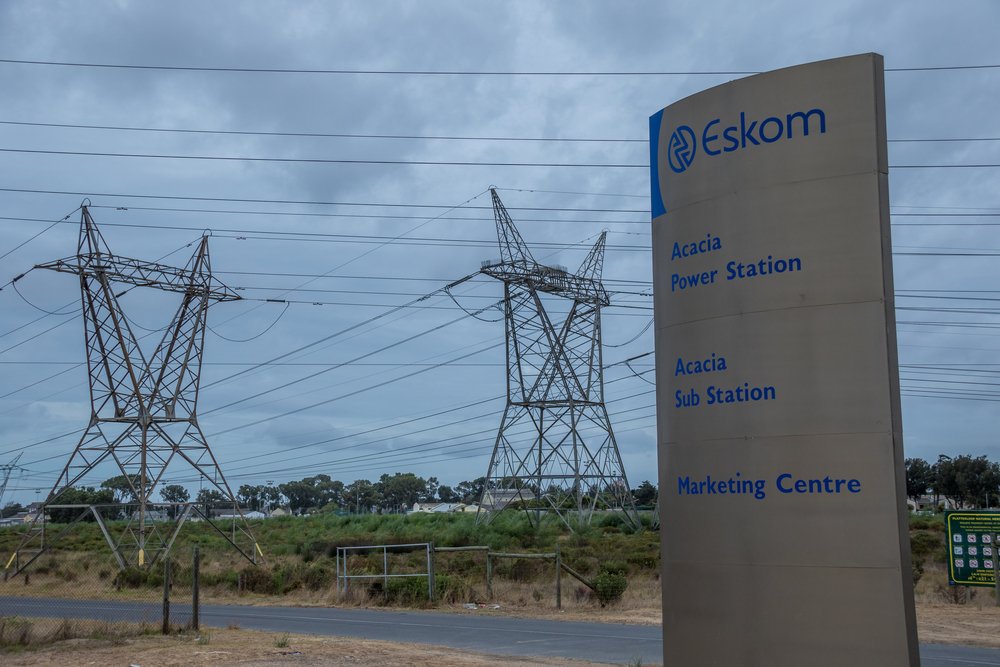

The electricity crisis is fundamentally a result of South Africa’s capitalist system and the policies implemented by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) over the last several decades. Eskom, once one of the world’s largest utility companies, currently supplies over 90% of South Africa’s electricity. However, since 2007, it has been unable to meet demand, forcing it to resort to scheduled blackouts to prevent a total collapse of the national grid.

In his State of the Nation Address in February 2023, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared the electricity crisis a national state of disaster under the Disaster Management Act, granting the government additional powers to tackle the situation. Ramaphosa also announced a cabinet reshuffle, creating a new Ministry of Electricity. However, these moves have been criticized as last-ditch efforts to manage a crisis that has its roots in mismanagement and systemic failings over the past two decades.

The electricity crisis is fundamentally a result of South Africa’s capitalist system and the policies implemented by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) over the last several decades. Eskom, once one of the world’s largest utility companies, currently supplies over 90% of South Africa’s electricity. However, since 2007, it has been unable to meet demand, forcing it to resort to scheduled blackouts to prevent a total collapse of the national grid.

Much of the blame for Eskom’s decline can be traced back to the ANC government’s shift toward neoliberal policies under former President Thabo Mbeki. In 1996, the government adopted the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy, which promoted privatization and public-private partnerships as models for delivering essential services, including electricity. The move away from state investment in public services led to a chronic underfunding of Eskom, resulting in a failure to maintain and expand power generation capacity. The national government did not authorize Eskom to increase its energy production until 2004, at which point it was already too late to meet the growing demand for electricity.

The legacy of these policies has been devastating. Between 1961 and 1996, the apartheid government commissioned the construction of 35,804 megawatts of electricity capacity. By contrast, since 1994, only 9,564 megawatts of capacity have been added, despite the construction of the Medupi and Kusile power plants. These new plants have been plagued by technical problems, delays, and cost overruns, while many of Eskom’s existing power stations, now over 50 years old, have continued to operate far beyond their intended lifespan, contributing to frequent breakdowns.

The privatization of coal mines has further exacerbated Eskom’s difficulties. Once state-owned, these mines are now controlled by private multinational corporations such as Glencore and Anglo American. Eskom is forced to purchase coal from these companies at inflated prices, driving up the cost of electricity production. At the same time, the government has increasingly turned to Independent Power Producers (IPPs) to supply electricity to the grid, often at higher prices than Eskom’s own generation costs. This shift has drained Eskom’s financial resources, leaving it unable to invest in extending the lifespan of its power stations or acquiring new capacity.

As of 2023, Eskom is burdened with approximately R400 billion in debt, much of it owed to international lenders such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The government’s decision to contract with private power producers has further deepened Eskom’s financial woes. In 2018, the then Minister of Energy, Jeff Radebe, signed a R56 billion contract with 27 additional IPPs, despite strong opposition from labor unions. These contracts guarantee payment to the IPPs, regardless of whether their electricity is needed, effectively siphoning resources away from Eskom’s ability to maintain and expand its own generation capacity.

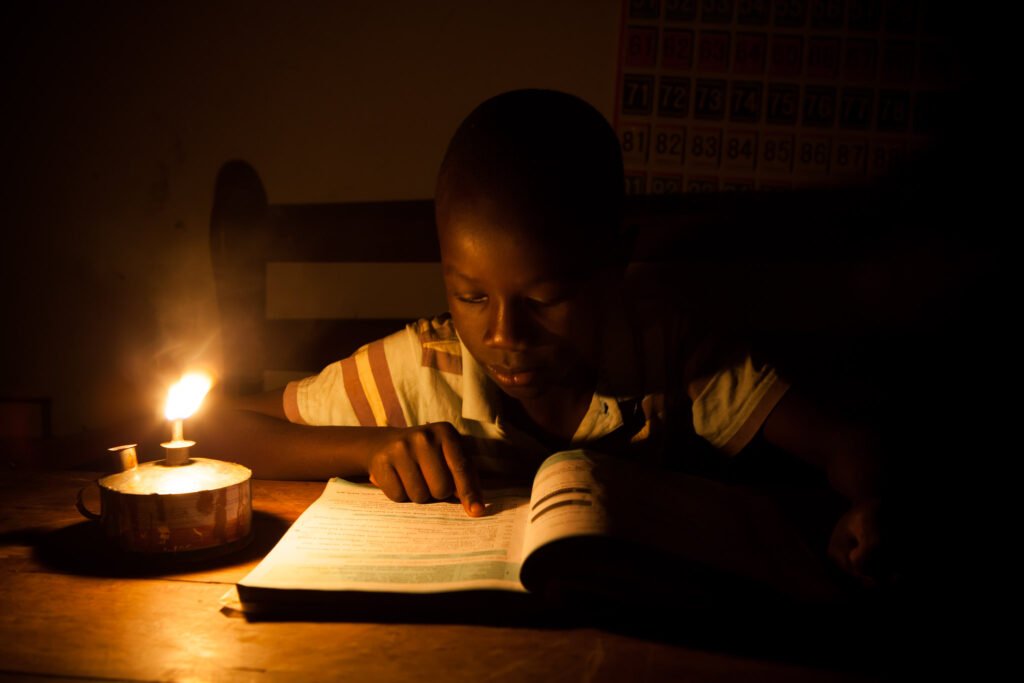

While wealthy South Africans can afford to mitigate the effects of load shedding by installing generators and solar panels, the working class bears the brunt of the crisis. Poor and working-class communities are forced to endure hours of power cuts each day, without access to alternative energy sources. To make matters worse, the national energy regulator has approved an 18.65% increase in electricity tariffs for the 2023-2024 financial year, further straining household budgets.

The energy crisis has sparked widespread anger across the country. Protests against continuous blackouts have erupted in major cities like Johannesburg and Durban, and opposition parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) have called for national shutdowns to pressure the government into addressing the crisis. However, many critics argue that single-day protests and shutdowns are insufficient to bring about the systemic change needed to resolve the crisis.

What is required, they argue, is a comprehensive re-nationalization of the coal mines and the cancellation of costly contracts with private power producers. Unions have called for greater investment in Eskom’s infrastructure, as well as a transition to renewable energy sources under democratic workers’ control. Only by placing the energy sector under the control of the working class, they assert, can South Africa achieve a reliable, affordable, and sustainable electricity supply.

In conclusion, South Africa’s energy crisis is not merely a technical issue but a symptom of deeper systemic problems rooted in the country’s capitalist system. The privatization of essential services, coupled with the mismanagement of Eskom, has led to an unsustainable situation that continues to harm the country’s economy and its people. To address this crisis, a radical transformation of the energy sector is needed—one that prioritizes the needs of the working class over the interests of private capital.