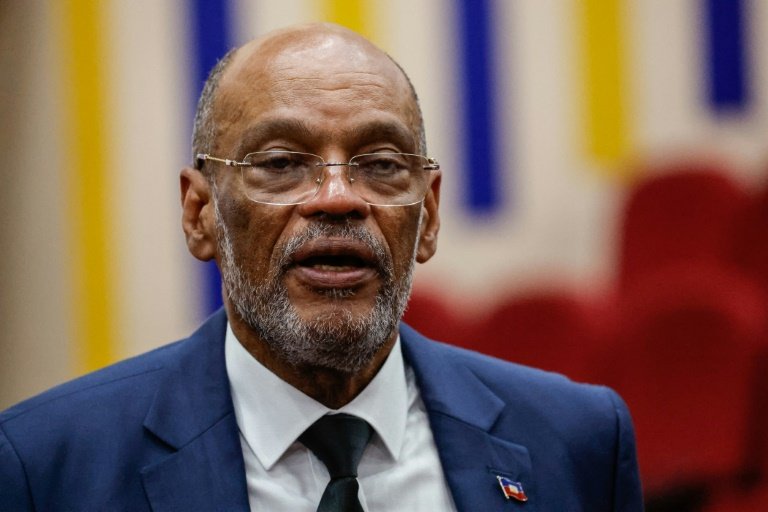

In March 2024, after months of escalating violence, Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigned from his position, marking another chapter in Haiti’s ongoing turmoil. His exit was precipitated by a gang-led insurrection that has taken control of much of Port-au-Prince. The U.S. government, seeing its influence over Haiti’s governance slipping, is now racing to broker a new transitional council to restore some semblance of order. However, with the Haitian state largely defunct and gang power expanding daily, the likelihood of real stability remains slim.

The recent uprising follows a brief period of relative calm after the emergence of the Bwa Kale movement, a grassroots effort formed by neighborhood self-defense groups aiming to counter gang violence.

Although effective in some areas, Bwa Kale lacked cohesion, and many neighborhoods became entangled in ongoing gang conflicts. Some self-defense groups even transformed into gangs themselves, while others, like the G9 alliance led by Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier, attempted to absorb the movement to bolster their own power.

The Rise of Chérizier and the Control of Port-au-Prince

By early 2024, gangs, under Chérizier’s leadership, controlled nearly 80 percent of Port-au-Prince. Their offensive has been relentless, with Chérizier openly calling for the toppling of Henry’s government and proclaiming a mission to wrest power from the state by any means necessary. This announcement was followed by a coordinated attack on the Solino neighborhood, an area that had previously resisted gang control. For Chérizier, securing Solino would enable his gangs to advance into other resistant neighborhoods, further tightening their grip over the capital.

As Henry’s regime weakened, the state’s ability to counter this wave of violence crumbled. While Henry repeatedly promised elections, none were held, leaving his regime isolated and illegitimate in the eyes of the Haitian population. The police and military, vastly outmatched by gang forces, were unable to reclaim significant territories. Though international intervention was considered, with the U.N. attempting to send a security force led by Kenya, legal and logistical hurdles rendered these efforts ineffective.

In February, as Henry visited Kenya in a last-ditch attempt to gain support, a new gang alliance, Viv Ansanm, launched an extensive assault on government institutions. They set ablaze over 600 homes and several police stations, with more than 5,000 prisoners breaking free during attacks on Haiti’s largest prisons.

By the time Henry attempted to return, the country’s airports and ports were effectively shut down, preventing his reentry. On March 12, Henry announced his resignation from abroad.

The U.S. Push for a Transitional Council

In response to Henry’s departure, the U.S., along with Caribbean allies, proposed the establishment of a transitional council. This nine-member body, consisting of representatives from various Haitian political factions and civil society groups, was designed to create a temporary authority until stability could be restored. Yet, the council’s viability remains uncertain. Many of the political parties that would comprise this council are deeply unpopular, seen by the Haitian public as complicit in the country’s corruption and ineffective governance.

Even before its official formation, the council faced internal divisions and opposition. Key political figures refused to participate, while some members of Pitit Desalin allied with figures like Guy Philippe, who had previously led a coup against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Additionally, on March 14, Chérizier issued threats against any leaders attempting to join the council, further undermining its prospects. He followed up these threats with attacks on a police academy and the national police chief’s residence, emphasizing his stance that Henry’s resignation was merely the beginning of his campaign.

An Unstable Future and the Risks of Foreign Intervention

With gangs controlling most of the capital and security forces unable to counter them, the U.N.’s plans for a peacekeeping mission appear increasingly unworkable. Kenya’s intended involvement was already complicated by its judiciary, which declared the mission unconstitutional. Following Henry’s resignation, Kenya put its plans on hold, and the U.S. is left scrambling to assemble a security force without direct military intervention. Canada, France, and other potential allies have refused to commit troops, wary of the risks and limited rewards of engaging in such a volatile environment.

Any potential U.N. mission would face significant obstacles. Haiti’s past experiences with U.N. peacekeepers, notably the MINUSTAH mission, left deep scars, including cholera outbreaks and reports of abuse. Such a mission would likely face substantial resistance from both armed gangs and a disillusioned Haitian public. The gangs, well-armed and deeply embedded within urban areas, are prepared for protracted conflict, turning any attempt at intervention into a complex urban war with unclear frontlines.

Moving Beyond Capitalism to Address Haiti’s Crisis

The Haitian crisis cannot be solved merely through military force. The country’s struggles are deeply tied to the systemic failures of capitalism, which has allowed gangs to thrive while leaving much of the population in poverty. For decades, political elites and the wealthy have collaborated with gangs to maintain power, embedding crime within the state itself. Under these conditions, any foreign intervention would likely serve only to reinforce the current capitalist framework that perpetuates inequality and despair.

Economic and social reforms are critical to providing lasting peace. Haitians need more than temporary security measures; they need opportunities for employment, decent housing, and accessible healthcare. Without addressing these root causes of instability, the cycle of violence will persist, and the gangs will continue to find recruits among disenfranchised communities. Even if external forces were to disarm current gang groups, the underlying issues of poverty and lack of opportunity would inevitably fuel future conflicts.

Chérizier’s claim to be a revolutionary leader may appeal to some, but his reliance on violence and domination offers no real path forward. A true solution for Haiti lies in dismantling the capitalist structures that have failed its people. Meaningful change would require expropriating the wealth of Haiti’s elite and transforming the country’s political and economic landscape to prioritize the needs of its workers and impoverished communities. Only through a revolutionary transformation, led by the Haitian people themselves, can Haiti hope to overcome its deep-seated crises and build a just society.